Top Online Casinos for Safe Gaming in 2026 – Top Real Money Casino Sites for USA Players

Discover the best online casinos real money options available to USA players in 2026. Our expert team has evaluated hundreds of real money online casinos to identify platforms that deliver secure transactions, verified payouts, and exceptional gaming experiences. Whether you’re searching for massive welcome bonuses, lightning-fast withdrawals, or extensive game libraries, this comprehensive guide reveals everything you need to know before depositing at any casino online real money site.

The online casino real money landscape has evolved dramatically, with operators now offering unprecedented security measures, diverse payment options including cryptocurrency, and thousands of games from world-class developers. Finding legitimate US online casinos requires understanding licensing requirements, bonus structures, and platform reliability—all factors we analyse in depth throughout this guide.

SlotoCash Casino

- Massive library of modern slots

- Lightning-fast withdrawals

- Daily reload bonuses

Captain Jack Casino

- Adaptive difficulty slots

- Generous welcome package

- Real-time tournament leaderboards

Slot Madness

- Retro-themed slot collections

- VIP progression system

- Fast dispute resolution

BetWhale

- Robust sportsbook integration

- One-click cash-out

- Live stats overlays

Las Atlantis Casino

- Cross-device session sync

- Weekly personalized missions

- Huge pool of progressive jackpots

Decode Casino

- Crypto-friendly platform

- Zero-fee transactions

- High-limit live tables

The Cocoa Casino

- Thousands of RNG games

- Transparent RTP data

- Friendly wagering policies

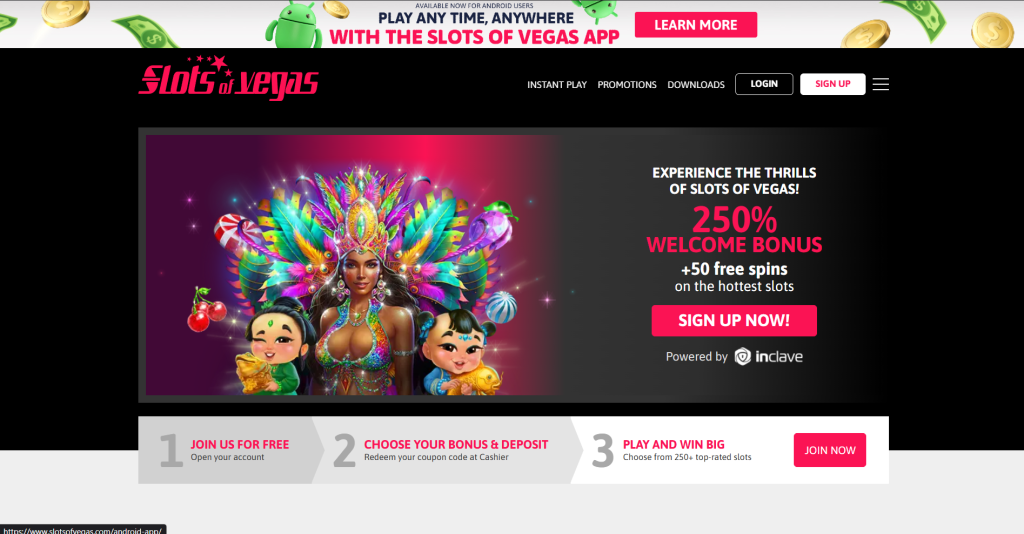

SlotsOfvegas

- Mobile-first design

- Auto-play customization

- 24/7 multilingual chat support

Raging Bull Casino

- Frequent free-spin drops

- Big jackpot network

- Low wagering requirements

Royal Ace Casino

- AI-driven game recommendations

- Personalized bonuses

- Smooth play on low-end devices

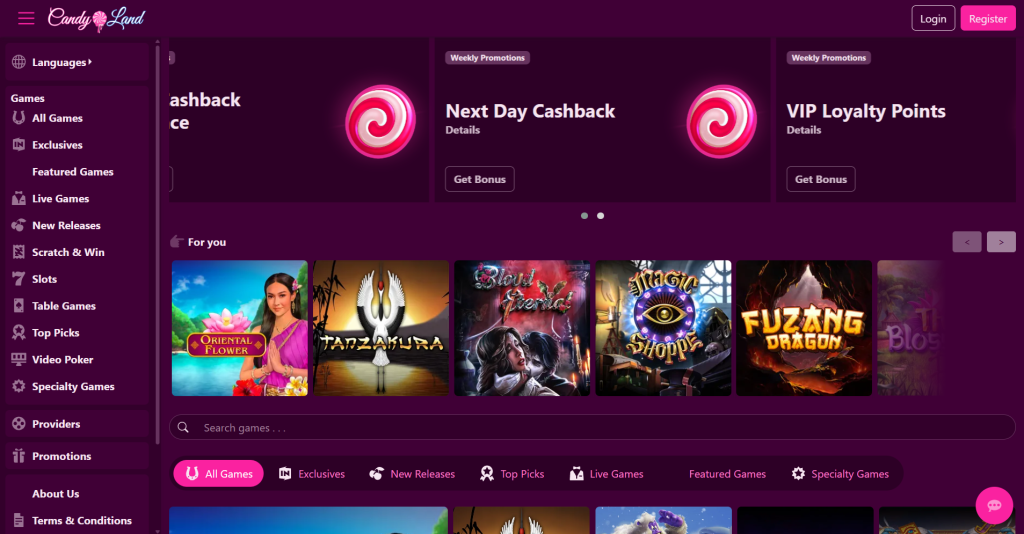

Candyland Casino

- Social play features

- Integrated in-game chat

- Achievement-based rewards

Donbet

- Beautiful UI/UX

- High-quality sound design

- Frequent mystery bonuses

Red Dog Casino

- Hardware-accelerated graphics

- Very fast loading times

- Player-driven game mods

RubySlots

- Blockchain-verified fairness

- Anonymous accounts

- Instant-win mini games

Paradise 8 Casino

- VR-compatible titles

- Ultra-low latency servers

- Crypto cashback

What Are Online Casinos Real Money?

Online casinos real money are digital gambling platforms where players wager actual currency on casino games including slots, table games, live dealer experiences, and specialty titles. Unlike social casinos or sweepstakes platforms that use virtual currencies, real money online casinos process genuine financial transactions—deposits fund your account, winnings accumulate as real cash, and withdrawals transfer funds directly to your bank account or e-wallet.

These platforms operate through sophisticated software that replicates traditional casino experiences digitally. Casino online real money sites partner with licensed game developers who create slot machines with verified Random Number Generators (RNGs), table games with mathematically accurate odds, and live dealer studios streaming professional dealers in real-time.

The defining characteristic separating online casinos USA from free-play alternatives involves monetary risk and reward. Every spin, hand, or bet carries actual financial stakes. Wins translate into withdrawable cash while losses reduce your bankroll. This fundamental element creates authentic gambling experiences accessible from any internet-connected device.

Key components of legitimate online casinos real money platforms:

- Licensed operations regulated by recognized gaming authorities

- Verified Random Number Generator certification for fair outcomes

- Secure encryption protecting financial transactions

- Multiple deposit and withdrawal options with reasonable limits

- Transparent bonus terms without hidden restrictions

- Professional customer support available 24/7

- Responsible gambling tools including deposit limits and self-exclusion

Modern top online casinos have matured significantly beyond early internet gambling sites. Today’s platforms feature HD graphics, immersive soundscapes, mobile-optimized interfaces, and game libraries rivaling major Las Vegas resorts. The convenience of playing anywhere combined with exclusive bonuses unavailable at land-based venues continues driving player migration toward digital platforms.

How to Get Started with Online Casinos Real Money

Getting started at online casinos real money platforms requires just a few straightforward steps. The entire process typically takes under ten minutes from initial registration to playing your first game.

Step 1: Choose a Reputable Platform

Selecting trustworthy real money online casinos represents the most critical decision you’ll make. Focus on operators holding valid licenses from recognized regulatory bodies. Our recommended casinos undergo rigorous evaluation covering security protocols, payout reliability, game fairness, and customer service quality before earning inclusion in this guide.

Step 2: Complete Registration

Creating your account involves providing basic personal information including your legal name, date of birth, email address, and residential address. US online casinos require this information for identity verification and regulatory compliance. Use accurate details matching your identification documents to avoid withdrawal complications.

Step 3: Verify Your Identity

Most casino online real money operators request identity verification before processing significant withdrawals. Prepare copies of government-issued photo identification (driver’s license or passport) and proof of address (utility bill or bank statement dated within 90 days). Completing verification proactively prevents payout delays when you’re ready to cash out winnings.

Step 4: Make Your First Deposit

Navigate to the cashier section and select your preferred payment method. Online casinos USA typically accept credit/debit cards, bank transfers, e-wallets like PayPal, and cryptocurrencies including Bitcoin. Minimum deposits usually range from $10-$25 depending on the platform and payment method selected.

Step 5: Claim Your Welcome Bonus

Most best online casinos offer generous welcome promotions for new players. These commonly include deposit match bonuses (100%-500% of your deposit), free spins on popular slots, or risk-free play credits. Enter any required bonus codes during the deposit process and review wagering requirements before claiming.

Step 6: Explore Games and Start Playing

With funds in your account, browse the game library and select titles matching your preferences. Top online casinos organize games by category—slots, table games, live dealer, specialty—with search filters for specific providers or features. Start with lower stakes while learning game mechanics before increasing bet sizes.

Pro tips for new players:

- Set a strict gambling budget before your first session

- Take advantage of demo modes to practice without risking money

- Read bonus terms completely before claiming promotions

- Enable responsible gambling tools from day one

- Start with games featuring higher RTP (Return to Player) percentages

Are Online Casinos Real Money Legal in the USA?

The legality of online casinos real money in the United States varies significantly by state. Following the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision enabling states to regulate their own gambling industries, several jurisdictions have legalized and launched regulated online casino markets.

States with fully legal online casino real money operations in 2026:

- New Jersey – Operating since 2013 with the most mature market

- Pennsylvania – Launched 2019 with extensive operator options

- Michigan – Active since 2021 with growing player base

- West Virginia – Legal since 2020 with multiple platforms

- Connecticut – Tribal-operated sites available since 2021

- Delaware – State-operated platform with limited options

Players residing in these jurisdictions can legally access licensed US online casinos operated by approved companies. These platforms pay state taxes, submit to regulatory oversight, and maintain player protection standards established by gaming commissions.

The offshore casino landscape:

Millions of American players access online casinos USA platforms operating from jurisdictions outside US borders. These offshore casinos—often licensed in Curaçao, Malta, or Panama—accept US players despite operating in a legal gray area. While federal law doesn’t explicitly prohibit individuals from gambling at offshore sites, these platforms lack domestic regulatory oversight.

Important considerations for offshore casinos:

- No US-based regulatory protection for disputes

- Varying reliability regarding withdrawal processing

- Potential banking complications with deposits/withdrawals

- Different responsible gambling standards than US-regulated sites

Our recommended real money online casinos include both state-regulated options where available and carefully vetted offshore operators with established track records. We prioritize platforms demonstrating consistent payout reliability, fair gaming practices, and responsive customer service regardless of licensing jurisdiction.

Factors we evaluate for legal compliance:

- Valid gambling licenses from recognized authorities

- Transparent terms and conditions

- Published payout percentages audited by independent agencies

- Segregated player funds protected from operational expenses

- Clear responsible gambling policies and tools

Players should understand their local laws before participating in online casino real money activities. Consulting state gaming commission websites provides authoritative information about currently legal options in your jurisdiction.

Deeper Dive into the Best Online Casinos Real Money

Our expert team has conducted extensive research to identify the top online casinos delivering exceptional experiences across every important metric. Each platform below has earned recommendation through demonstrated excellence in security, game variety, bonus value, and payout reliability.

These real money online casinos represent the industry’s finest options for USA players seeking trustworthy gambling experiences. We’ve analyzed welcome bonuses, withdrawal speeds, customer support quality, and overall user experience to compile this definitive ranking.

#1. SlotoCash Casino – Premier Destination for Modern Slot Enthusiasts

SlotoCash Casino has established itself as a dominant force among online casinos real money platforms, earning our top recommendation through consistent excellence across every evaluation category. This veteran operator combines a massive game library with lightning-fast payouts and generous promotional offerings that keep players returning year after year.

The platform’s commitment to player satisfaction shows in every detail. From the moment you land on their polished interface, navigation feels intuitive and responsive. Game categories are clearly organized, account management requires minimal clicks, and promotional offers display prominently without overwhelming the user experience.

What truly distinguishes SlotoCash from competing casino online real money sites is their withdrawal processing speed. Where many operators make players wait days or even weeks for payouts, SlotoCash consistently delivers funds within 24-48 hours across most payment methods. This reliability has earned them exceptional trust among serious gamblers who prioritize access to their winnings.

SlotoCash Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | $600 Welcome Match + 60 Free Spins |

| Bonus Code | 600CASINO |

| Rating | 9.4/10 |

| Game Library | 200+ RTG Slots, Table Games, Video Poker |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $25 |

| Withdrawal Time | 24-48 Hours |

| Payment Methods | Credit Cards, Bitcoin, Litecoin, Bank Wire |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – iOS and Android optimized |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email, Phone |

SlotoCash’s game selection focuses heavily on RTG (RealTime Gaming) content, featuring both classic favorites and cutting-edge new releases. Their progressive jackpot network regularly produces six-figure winners, while specialty games including keno and scratch cards provide variety beyond traditional casino offerings.

Pros:

- Massive library of modern slots with frequent new releases

- Lightning-fast withdrawals compared to industry averages

- Daily reload bonuses keeping bankrolls healthy

- Cryptocurrency support for enhanced privacy and speed

- Established operator with 15+ years of reliable service

- Generous 600% welcome bonus across multiple deposits

Cons:

- Primarily RTG games limits variety for some players

- Higher wagering requirements on certain promotions

- No live dealer games currently available

#2. Captain Jack Casino – Generous Welcome Package with Tournament Action

Captain Jack Casino delivers an adventure-themed gambling experience that combines generous bonuses with exciting competitive elements. This online casino real money platform has cultivated a loyal following through consistently rewarding promotions and engaging tournament offerings that add competitive dimensions beyond standard casino play.

The nautical theme permeates every aspect of Captain Jack’s presentation, from the treasure chest-laden interface to the pirate-inspired promotional copy. While aesthetics remain secondary to substance, this cohesive design creates a memorable experience distinguishing Captain Jack from generic competitors flooding the US online casinos market.

Tournament functionality represents Captain Jack’s standout feature among real money online casinos. Regular slot tournaments pit players against each other for prize pools, adding strategic elements and social competition missing from solitary gambling sessions. Real-time leaderboards track standings throughout events, creating genuine excitement as positions shift with every spin.

Captain Jack Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 200% Bonus + 35 Free Spins |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.4/10 |

| Game Library | 150+ Slots, Table Games, Specialty |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $30 |

| Withdrawal Time | 2-5 Business Days |

| Payment Methods | Visa, Mastercard, Bitcoin, Bank Wire |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Responsive Design |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

The 200% welcome bonus stretching across your first deposits provides substantial value for new players. Combined with free spins on popular slot titles, Captain Jack’s onboarding package ranks among the most generous available at legitimate online casinos USA operators.

Pros:

- Adaptive difficulty slots adjusting to player preferences

- Generous welcome package without excessive restrictions

- Real-time tournament leaderboards adding competitive excitement

- No bonus code required simplifying registration

- Regular promotional refreshes keeping offers exciting

- Responsive customer support resolving issues promptly

Cons:

- Limited game provider variety with RTG focus

- Withdrawal processing can extend beyond 48 hours

- Fewer progressive jackpot options than competitors

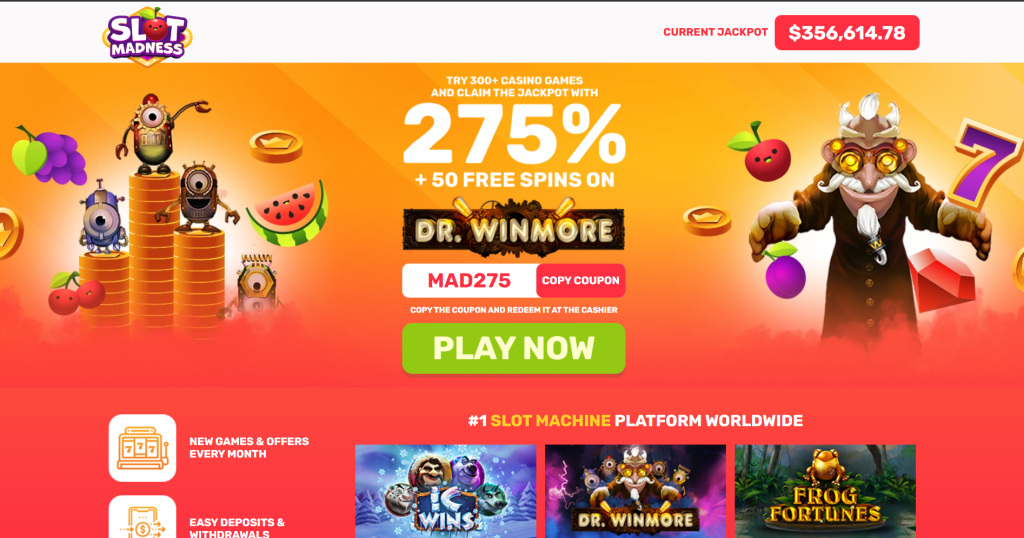

#3. Slot Madness – Retro Gaming Meets Modern VIP Rewards

Slot Madness carves a unique niche within the online casinos real money landscape by celebrating classic gaming aesthetics while delivering thoroughly modern features. Their VIP progression system stands among the industry’s most rewarding loyalty programs, providing tangible benefits that increase alongside your play volume.

The “madness” branding reflects genuinely frantic promotional activity. Slot Madness runs more concurrent bonus offers than most competitors, creating constant opportunities to boost your bankroll through deposit matches, free spin packages, and cashback deals. Players who maximize these promotions extract exceptional value impossible to replicate at land-based casinos.

Dispute resolution deserves special recognition when evaluating this casino online real money operator. Slot Madness maintains dedicated support teams specifically handling player complaints, ensuring concerns receive professional attention rather than getting lost in generic ticket queues. This commitment to fair resolution builds trust crucial for long-term player relationships.

Slot Madness Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 275% Bonus + 50 Free Spins |

| Bonus Code | MAD275 |

| Rating | 9.4/10 |

| Game Library | 175+ Slots, Table Games, Video Poker |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $25 |

| Withdrawal Time | 2-5 Business Days |

| Payment Methods | Visa, Mastercard, Crypto, eCheck |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Mobile Optimized |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email, Phone |

The VIP progression system rewards consistent play with increasingly valuable benefits. Tier advancement unlocks higher withdrawal limits, personalized bonuses, dedicated account managers, and exclusive promotional access. High-volume players find exceptional value in Slot Madness’s structured loyalty rewards.

Pros:

- Retro-themed slot collections appealing to classic gaming fans

- Comprehensive VIP progression system with meaningful rewards

- Fast dispute resolution through dedicated support teams

- 275% welcome bonus among highest available percentages

- Frequent promotional rotations providing fresh opportunities

- Multiple cryptocurrency options for deposits and withdrawals

Cons:

- Retro aesthetic may not appeal to all players

- VIP benefits require significant play volume to unlock

- Limited live gaming options

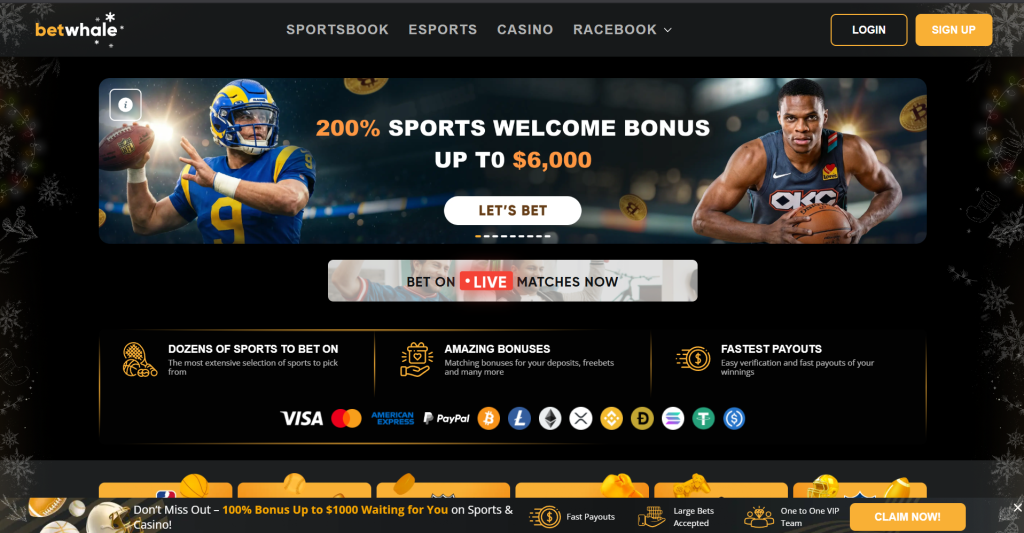

#4. BetWhale – Where Casino Gaming Meets Sports Betting Excellence

BetWhale represents the new generation of online casinos real money platforms integrating comprehensive sportsbook functionality alongside traditional casino gaming. This hybrid approach appeals to players seeking varied gambling experiences within single accounts, eliminating the hassle of managing multiple platform relationships.

The one-click cash-out feature distinguishes BetWhale’s user experience from competitors requiring multiple confirmation steps for withdrawals. When you’re ready to access your winnings, a single tap initiates the payout process without navigating through layers of menus or answering repetitive security questions. This streamlined approach reflects BetWhale’s broader commitment to player convenience.

Live stats overlays enhance both sports betting and casino gaming at BetWhale. Real-time data integration helps informed decision-making whether you’re analyzing odds for upcoming matches or tracking game performance during slots sessions. This data-driven approach attracts analytical players appreciating transparency and information access.

BetWhale Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 100% Match Up to $1000 |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.4/10 |

| Game Library | 1000+ Casino Games, Full Sportsbook |

| Software Providers | Multiple Top-Tier Developers |

| Minimum Deposit | $20 |

| Withdrawal Time | 24-72 Hours |

| Payment Methods | Cards, Crypto, E-wallets, Bank Transfer |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Native Apps Available |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

BetWhale’s game library dwarfs single-focus casino platforms by incorporating content from multiple software providers. This diversity ensures something for every preference, from classic three-reel slots to elaborate video slots featuring cinematic productions, plus comprehensive table game and live dealer sections.

Pros:

- Robust sportsbook integration within single platform

- One-click cash-out eliminating withdrawal friction

- Live stats overlays providing valuable data insights

- Massive game library exceeding 1000 titles

- Multiple software providers ensuring game variety

- Competitive odds on sports betting markets

Cons:

- Jack-of-all-trades approach may lack specialization depth

- Newer operator with shorter track record than veterans

- Welcome bonus percentage lower than some competitors

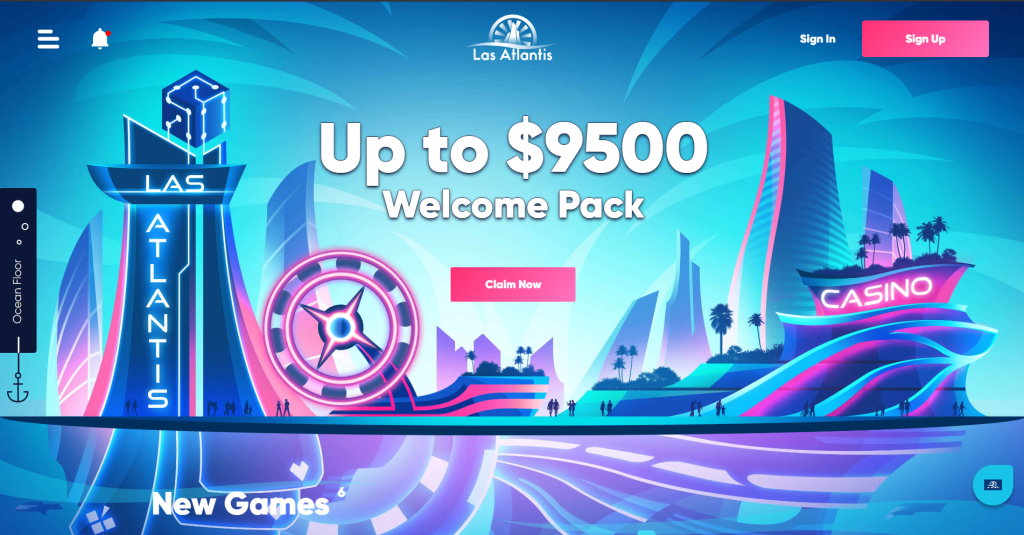

#5. Las Atlantis Casino – Underwater Adventure with Massive Welcome Package

Las Atlantis Casino immerses players in an oceanic fantasy realm while delivering one of the most substantial welcome packages available at online casinos real money platforms. The up to $9,500 spread across multiple deposits provides extended bankroll support for new players exploring this underwater kingdom’s offerings.

Cross-device session synchronization sets Las Atlantis apart technically from competitors requiring separate logins across devices. Start a gaming session on your desktop computer, continue seamlessly on your smartphone during commute, and finish on your tablet before bed—all without losing progress or needing repeated authentications.

Weekly personalized missions gamify the experience beyond basic slot spinning. These customized challenges reward completion with bonus funds, free spins, or other perks, creating objectives that structure play sessions productively. The mission system transforms passive gambling into active achievement hunting.

Las Atlantis Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | Up to $9500 Welcome Pack |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.4/10 |

| Game Library | 200+ RTG Games |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $30 |

| Withdrawal Time | 2-5 Business Days |

| Payment Methods | Visa, Mastercard, Neosurf, Bitcoin |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Fully Responsive |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

The progressive jackpot network at Las Atlantis connects multiple games into shared prize pools that can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars. Every qualifying spin contributes to these growing jackpots, creating life-changing winning potential from routine gaming sessions.

Pros:

- Cross-device session sync for seamless multi-platform play

- Weekly personalized missions adding gamification elements

- Huge pool of progressive jackpots with six-figure potential

- Massive $9,500 welcome package across deposits

- Immersive underwater theme creating unique atmosphere

- Reliable RTG software with proven fairness

Cons:

- RTG exclusivity limits game variety

- Extended withdrawal processing compared to fastest options

- Theme may not appeal to all player preferences

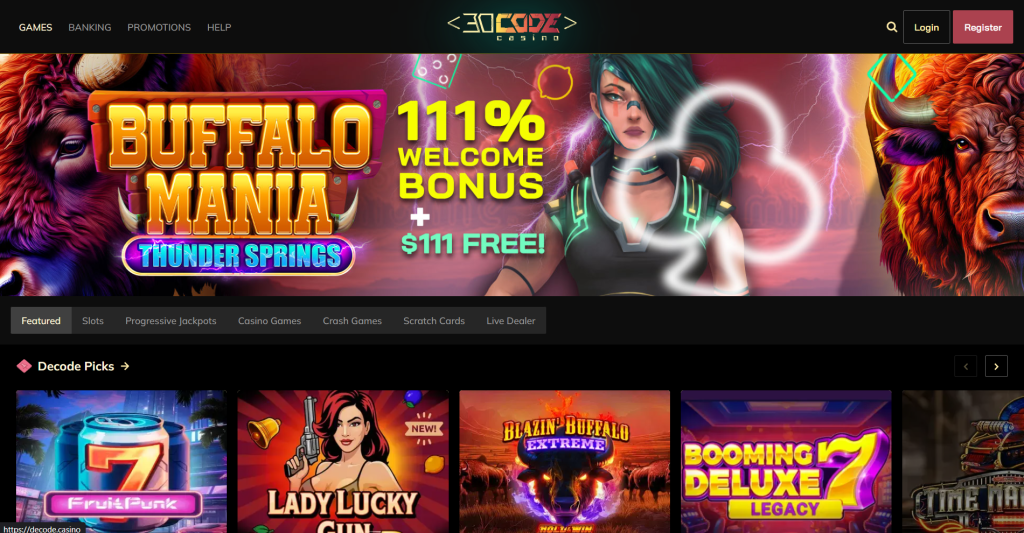

#6. Decode Casino – Crypto-Forward Platform with Zero-Fee Transactions

Decode Casino has positioned itself as the premier cryptocurrency-friendly option among real money online casinos, eliminating transaction fees entirely for crypto deposits and withdrawals. This approach saves players significant money over time while providing the enhanced privacy and speed cryptocurrency transactions enable.

The zero-fee policy extends meaningful value particularly for frequent depositors and withdrawers. Traditional payment methods often incur 2-5% processing fees at many online casinos USA platforms, costs that accumulate substantially for active players. Decode’s fee elimination represents genuine savings translating directly to increased bankroll value.

High-limit live tables cater to serious gamblers seeking stakes matching land-based VIP rooms. Where many online platforms cap table limits at modest levels, Decode accommodates high rollers wanting significant action. This flexibility attracts experienced players frustrated by restrictive limits elsewhere.

Decode Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 500% Match Bonus + 50 Free Spins |

| Bonus Code | 500CASH |

| Rating | 9.3/10 |

| Game Library | 200+ Games Including Live Dealer |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $25 |

| Withdrawal Time | 24-48 Hours (Crypto) |

| Payment Methods | Bitcoin, Litecoin, Visa, Mastercard |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Mobile Optimized |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

The 500% welcome bonus represents one of the highest match percentages available at legitimate casino online real money sites. Combined with 50 free spins, this package delivers exceptional starting value for players willing to meet the associated wagering requirements.

Pros:

- Crypto-friendly platform with zero-fee transactions

- Zero-fee transactions saving significant money over time

- High-limit live tables accommodating serious gamblers

- Massive 500% welcome bonus percentage

- Fast cryptocurrency withdrawals within 24-48 hours

- Live dealer options adding authentic casino atmosphere

Cons:

- Higher bonus wagering requirements than some competitors

- Traditional payment methods have slower processing

- Game library smaller than multi-provider platforms

#7. Slots of Vegas – Mobile-First Design with Customization Excellence

Slots of Vegas delivers precisely what its name promises—an authentic Vegas slots experience optimized for modern mobile devices. Their mobile-first development approach ensures smartphone and tablet users enjoy feature-complete functionality without the compromises plaguing many desktop-to-mobile ports at competing online casinos real money platforms.

Auto-play customization reaches unprecedented depth at Slots of Vegas. Configure exactly how automated spins behave—stop on bonus triggers, pause at certain win thresholds, adjust between spin delays, or continue until bankroll depletes. This granular control lets players craft personalized automated experiences matching their preferences precisely.

Multilingual support operates around the clock with native speakers rather than translation software. This commitment to genuine communication ensures players receive helpful support regardless of language barriers, building trust through authentic human interaction rather than frustrating automated responses.

Slots of Vegas Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | $2500 Match Bonus + 50 Free Spins |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.2/10 |

| Game Library | 200+ RTG Slots and Games |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $25 |

| Withdrawal Time | 3-5 Business Days |

| Payment Methods | Visa, Mastercard, Bitcoin, Bank Wire |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Mobile-First Design |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Multilingual Live Chat |

The $2,500 welcome bonus spread across deposits provides substantial support for exploring Slots of Vegas’s extensive game library. Free spins on popular titles let you sample premium content without additional cost during your onboarding experience.

Pros:

- Mobile-first design optimized for smartphone gaming

- Auto-play customization offering unprecedented control

- 24/7 multilingual chat support with native speakers

- $2,500 welcome package with free spins included

- Vegas-authentic slot gaming experience

- Wide cryptocurrency acceptance for deposits/withdrawals

Cons:

- Withdrawal processing slower than industry leaders

- RTG exclusivity limiting game variety

- Interface may feel dated compared to newer platforms

#8. Raging Bull Casino – Jackpot Network Power with Player-Friendly Terms

Raging Bull Casino charges into the online casinos real money space with an aggressive promotional stance and one of the industry’s most rewarding progressive jackpot networks. The combination of frequent free-spin promotions and low wagering requirements creates exceptional value for players understanding how to maximize available offers.

The big jackpot network aggregates contributions across multiple games and players into prize pools that can reach staggering sums. Every qualifying bet from every connected player feeds these growing jackpots, meaning life-changing wins can trigger from any session. Raging Bull’s network consistently produces major winners.

Low wagering requirements represent perhaps Raging Bull’s greatest competitive advantage among US online casinos. Where many operators impose 40x-60x playthrough demands, Raging Bull frequently offers promotions with 25x-30x requirements. This difference dramatically improves actual clearing probability, transforming bonuses from theoretical to practical value.

Raging Bull Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 50 Free Spins + 250% Bonus |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.2/10 |

| Game Library | 200+ Games Including Jackpots |

| Software Provider | RealTime Gaming (RTG) |

| Minimum Deposit | $30 |

| Withdrawal Time | 3-5 Business Days |

| Payment Methods | Credit Cards, Bitcoin, Bank Wire |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Fully Responsive |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

The no-deposit free spins component of Raging Bull’s welcome offer provides risk-free introduction to their platform. These complimentary spins let you experience game quality and interface functionality before committing personal funds.

Pros:

- Frequent free-spin drops keeping play exciting

- Big jackpot network with life-changing potential

- Low wagering requirements improving bonus value

- Free spins available without deposit required

- Established reputation with consistent payouts

- Strong RTG game selection with regular updates

Cons:

- Withdrawal times extend beyond fastest competitors

- Limited payment method selection

- Customer support occasionally slow during peak periods

#9. Candyland Casino – Social Gaming Innovation with Achievement Systems

Candyland Casino reimagines casino online real money gaming through social features and gamification elements traditionally associated with video games rather than gambling platforms. This innovative approach attracts younger demographics and players seeking community engagement beyond solitary slot spinning.

The integrated in-game chat system enables real-time communication with fellow players during sessions. Share reactions to big wins, discuss strategy, or simply enjoy social interaction while gambling. This community element adds enjoyment dimensions completely absent from traditional online casinos USA experiences.

Achievement-based rewards transform gambling into objective-oriented gameplay. Complete specific challenges—hit certain combinations, reach betting milestones, explore new games—and unlock bonuses, free spins, or exclusive content. This progression system provides satisfying goals structuring play sessions productively.

Candyland Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 200% Welcome Bonus |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.2/10 |

| Game Library | 150+ Games |

| Software Provider | Multiple Providers |

| Minimum Deposit | $25 |

| Withdrawal Time | 2-5 Business Days |

| Payment Methods | Cards, Crypto, E-wallets |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Mobile Optimized |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

Candyland’s whimsical aesthetic creates a lighthearted atmosphere distinguishing it from serious-toned competitors. The colorful interface and playful design appeal to players seeking entertainment-focused experiences rather than intimidating high-stakes environments.

Pros:

- Social play features enabling player interaction

- Integrated in-game chat for community building

- Achievement-based rewards adding gamification depth

- Welcoming aesthetic appealing to casual players

- Multiple software providers ensuring variety

- Straightforward 200% welcome bonus

Cons:

- Smaller game library than major competitors

- Social features may distract serious gamblers

- Achievement system requires significant time investment

#10. Donbet – Premium Design Experience with Mystery Bonus Drops

Donbet rounds out our top online casinos recommendations with a platform prioritizing premium user experience above all else. The beautiful UI/UX design represents some of the finest interface work in online gambling, creating genuinely enjoyable navigation and visual experiences throughout every interaction.

High-quality sound design accompanies the visual excellence. Game audio, ambient effects, and interface sounds receive attention typically reserved for console video games. Players using quality headphones or speakers notice dramatic atmospheric improvements compared to competitors treating audio as afterthought.

Mystery bonuses drop frequently without announcement or requirement, surprising players with unexpected rewards during normal sessions. These random promotions—ranging from free spins to bonus credits to cashback offers—create exciting unpredictability rewarding consistent play.

Donbet Casino Specifications:

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Welcome Bonus | 10% Cashback on Crypto Deposits |

| Bonus Code | No Code Required |

| Rating | 9.2/10 |

| Game Library | 3000+ Games |

| Software Providers | 50+ Top Developers |

| Minimum Deposit | $20 |

| Withdrawal Time | 24-48 Hours |

| Payment Methods | Crypto, Cards, E-wallets |

| Mobile Compatible | Yes – Native Apps Available |

| Customer Support | 24/7 Live Chat, Email |

Donbet’s massive 3000+ game library sourced from over 50 developers dwarfs single-provider competitors. This variety ensures every player preference finds satisfaction, from classic RTG slots to cutting-edge releases from industry innovators like NetEnt and Pragmatic Play.

Pros:

- Beautiful UI/UX setting industry design standards

- High-quality sound design enhancing immersion

- Frequent mystery bonuses rewarding regular play

- Massive 3000+ game library with 50+ providers

- Fast cryptocurrency withdrawals within 24-48 hours

- Ongoing 10% crypto cashback providing consistent value

Cons:

- Welcome bonus structure less generous than competitors

- Premium experience may feel overwhelming for newcomers

- Crypto-focused approach less convenient for traditional payment users

Types of Online Casino Real Money Bonuses

Understanding bonus structures helps maximize value when playing at online casinos real money platforms. Operators utilize various promotional mechanics to attract and retain players, each with distinct advantages and requirements worth understanding thoroughly.

Welcome Bonuses

First-deposit incentives represent the most valuable promotions available at real money online casinos. These typically match your initial deposit by a percentage—100%, 200%, or even 500%—up to specified limits. A 200% match on a $100 deposit provides $200 in bonus funds, tripling your starting bankroll.

No-Deposit Bonuses

Risk-free promotions credit bonus funds or free spins without requiring deposits. These offers let players sample casino online real money platforms before committing personal funds. Amounts typically range from $10-$50 in bonus credits or 10-100 free spins on selected slots.

Free Spins Packages

Complimentary slot spins on designated games provide bonus value without direct fund deposits. These often accompany welcome packages or appear as standalone promotions. Winnings from free spins typically carry wagering requirements before withdrawal eligibility.

Reload Bonuses

Subsequent deposit incentives reward existing players with match percentages smaller than welcome offers but available repeatedly. Regular reload promotions maintain bankroll value for consistent players.

Cashback Offers

Loss-recovery promotions return percentages of net losses over specified periods. Typical cashback ranges from 5-25% on weekly or monthly losses, providing safety nets during unlucky streaks.

VIP and Loyalty Rewards

Progressive benefit programs reward cumulative play volume with increasingly valuable perks. Higher tiers unlock better bonuses, faster withdrawals, dedicated support, and exclusive promotional access.

Critical bonus terms to understand:

- Wagering Requirements – Total betting volume required before bonus funds become withdrawable

- Game Contributions – Different games count differently toward wagering (slots typically 100%, table games 10-20%)

- Time Limits – Deadlines for meeting requirements before bonus expiration

- Maximum Bets – Betting limits while bonus funds remain active

- Maximum Cashouts – Withdrawal caps on bonus-derived winnings

What Games Can You Play at Online Casinos Real Money?

The best online casinos offer thousands of games spanning every category imaginable. Understanding available options helps identify platforms matching your preferences and playing style.

Slot Machines

Slots dominate online casinos real money game libraries, typically comprising 70-90% of available titles. Categories include classic three-reel games, elaborate video slots with bonus features, progressive jackpots offering life-changing prizes, and Megaways titles featuring variable reel mechanics.

Popular slot themes span mythology, adventure, movies, music, nature, and fantasy. Features include free spin rounds, expanding wilds, multipliers, cascading reels, and bonus mini-games. RTP (Return to Player) percentages typically range from 94-98%, indicating long-term expected returns.

Table Games

Classic casino table games translate perfectly to digital formats at real money online casinos. Blackjack variants include classic, European, Vegas Strip, and multi-hand options. Roulette offerings feature American (double-zero), European (single-zero), and French versions with varying house edges.

Baccarat, craps, and poker variants round out table selections. Each game maintains mathematically accurate odds matching physical casino versions, with RNG certification ensuring fair outcomes.

Live Dealer Games

Professional dealers operate real casino equipment in studio settings, streaming games in real-time to players worldwide. Live blackjack, roulette, baccarat, and poker provide authentic casino atmosphere impossible to replicate through purely digital games.

High-definition video streams show every card shuffle and wheel spin, with chat functions enabling dealer and player interaction. Live gaming combines convenience of online access with social elements of traditional casinos.

Video Poker

Strategy-based poker machines offer some of the highest RTPs available at online casinos USA. Jacks or Better, Deuces Wild, and Joker Poker variants provide skilled players with edges unavailable in pure chance games. Optimal strategy reduces house advantages below 1% on select titles.

Specialty Games

Alternative options include keno (lottery-style number matching), scratch cards (instant win tickets), bingo, and various arcade-style games. These titles provide variety beyond traditional casino offerings.

Payment Methods at US Online Casinos

Top online casinos support diverse payment options accommodating various player preferences and regional availability. Understanding each method’s advantages and limitations helps select optimal approaches for your situation.

Credit and Debit Cards

Visa and Mastercard provide familiar deposit methods accepted nearly universally. Transactions process instantly, though some banks decline gambling-related charges. Withdrawals to cards typically require 3-5 business days and may face additional banking restrictions.

E-Wallets

PayPal, Skrill, Neteller, and similar services offer convenient intermediaries between banks and casinos. Deposits process instantly while withdrawals typically complete within 24-48 hours. E-wallets provide privacy by avoiding direct bank-casino connections.

Cryptocurrencies

Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and other digital currencies enable the fastest transactions available at online casinos real money platforms. Deposits confirm within minutes while withdrawals process in hours rather than days. Enhanced privacy and often fee-free transactions make crypto increasingly popular.

Bank Transfers

Direct wire transfers accommodate larger transactions but require extended processing periods (3-7 business days). ACH transfers provide domestic alternatives with similar timelines. These methods suit players comfortable with longer waits for larger sums.

Prepaid Options

Paysafecard, Play+, and similar prepaid methods enable deposits without connecting personal accounts. These options provide privacy and spending control, though withdrawal capabilities vary by platform.

| Payment Method | Deposit Speed | Withdrawal Speed | Typical Fees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credit/Debit Cards | Instant | 3-5 Business Days | 0-3% |

| E-Wallets | Instant | 24-48 Hours | 0-2% |

| Cryptocurrency | 10-60 Minutes | 1-24 Hours | Network fees only |

| Bank Transfer | 1-5 Business Days | 3-7 Business Days | Varies |

| Prepaid Cards | Instant | N/A (deposit only) | 0-5% |

How We Rate Online Casinos Real Money Platforms

Our evaluation methodology ensures recommendations meet rigorous standards across every important metric. Understanding our criteria helps players assess platforms independently using these same frameworks.

Licensing and Regulation

Verified licenses from recognized authorities form the foundation of trustworthiness. We confirm regulatory credentials, check for disciplinary actions, and verify ongoing compliance with oversight requirements.

Security Infrastructure

Advanced encryption, secure payment processing, and data protection protocols protect player information and funds. We evaluate SSL certification, payment security standards, and privacy policies thoroughly.

Game Fairness

Independent RNG certification from agencies like eCOGRA or Gaming Labs ensures games produce truly random outcomes. Published RTP percentages and regular audits demonstrate ongoing fairness commitment.

Bonus Value

Welcome packages and ongoing promotions provide genuine value when terms remain reasonable. We assess wagering requirements, time limits, game restrictions, and overall clearability when evaluating bonuses.

Payout Reliability

Consistent, timely withdrawal processing separates trustworthy operators from problematic ones. We verify processing speeds across payment methods and investigate player reports regarding payout issues.

Customer Support

Responsive, helpful assistance available through multiple channels demonstrates player care. We test response times, solution quality, and agent knowledge through direct interactions.

User Experience

Intuitive navigation, mobile optimization, and overall design quality impact daily enjoyment. We evaluate interface functionality across devices and assess usability for various player types.

Best Online Casino Real Money Games This Month

Our experts continuously monitor online casinos real money game releases and player trends to identify standout titles worth your attention. These recommendations combine entertainment value, favorable return percentages, and proven popularity among experienced players.

Top Slot Recommendations for 2026

Mega Moolah Progressive

This legendary progressive jackpot slot from Microgaming has created more millionaires than any other online slot machine. The African safari theme provides entertaining gameplay while four-tiered jackpots—Mini, Minor, Major, and Mega—offer escalating prize potential. The Mega jackpot regularly exceeds $10 million, making every spin potentially life-changing.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Microgaming |

| RTP | 88.12% (lower due to jackpot contribution) |

| Volatility | Medium |

| Maximum Win | Progressive Jackpot (Unlimited) |

| Minimum Bet | $0.25 |

| Paylines | 25 Fixed |

| Special Features | Free Spins, Multipliers, Jackpot Wheel |

Gates of Olympus

Pragmatic Play’s Greek mythology masterpiece dominates real money online casinos through its innovative tumble mechanics and massive multiplier potential. Symbols cascade rather than spin, with consecutive wins building multipliers up to 500x. The buy-bonus feature lets impatient players purchase direct access to the lucrative free spins round.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Pragmatic Play |

| RTP | 96.50% |

| Volatility | High |

| Maximum Win | 5,000x Stake |

| Minimum Bet | $0.20 |

| Paylines | Scatter Pays (All Positions) |

| Special Features | Tumble Feature, Multipliers, Free Spins, Ante Bet |

Sweet Bonanza

Another Pragmatic Play sensation, Sweet Bonanza delivers candy-coated excitement through cluster pays and bomb multipliers. The colorful confectionery theme appeals broadly while high volatility rewards patient players with explosive winning potential. This title consistently ranks among the most-played slots at top online casinos worldwide.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Pragmatic Play |

| RTP | 96.51% |

| Volatility | High |

| Maximum Win | 21,175x Stake |

| Minimum Bet | $0.20 |

| Paylines | Scatter Pays |

| Special Features | Tumble Feature, Free Spins, Multiplier Bombs |

Book of Dead

Play’n GO’s Egyptian adventure remains the gold standard for book-style slots at casino online real money platforms. Rich the explorer guides players through ancient tombs seeking expanding symbols that can fill entire reels during free spins. The balanced volatility provides consistent entertainment without excessive bankroll swings.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Play’n GO |

| RTP | 96.21% |

| Volatility | High |

| Maximum Win | 5,000x Stake |

| Minimum Bet | $0.10 |

| Paylines | 10 Fixed |

| Special Features | Free Spins, Expanding Symbols, Gamble Feature |

Featured Table Games

Lightning Roulette

Evolution Gaming’s electrifying roulette variant adds random multipliers up to 500x on straight-up number bets. The innovative format combines traditional roulette mechanics with lottery-style excitement, creating thrilling anticipation as lightning strikes random numbers each round. This title revolutionized live dealer gaming at online casinos USA platforms.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Evolution Gaming |

| Game Type | Live Dealer Roulette |

| RTP | 97.30% |

| Multipliers | 50x – 500x on Straight Bets |

| Minimum Bet | $0.20 |

| Maximum Bet | Varies by Casino |

| Special Features | Random Lightning Multipliers, HD Streaming |

Blackjack Perfect Pairs

This popular blackjack variant adds side bet excitement to the classic card game. The Perfect Pairs wager pays when your first two cards form a pair, with mixed, colored, and perfect pairs offering escalating payouts. Main game strategy remains unchanged, allowing skilled players to minimize house edge while enjoying additional winning opportunities.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Multiple Providers |

| Game Type | Table Game / Live Dealer |

| Main Game RTP | 99.50%+ (with optimal strategy) |

| Side Bet RTP | 95.90% |

| Minimum Bet | $1.00 |

| Special Features | Perfect Pairs Side Bet, Insurance, Split, Double Down |

Casino Hold’em

Poker enthusiasts appreciate this heads-up variant pitting players against the dealer rather than other participants. Strategic decisions regarding calling or folding influence outcomes, providing skill-based gameplay missing from pure chance games. The AA bonus side bet adds jackpot potential for premium starting hands.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Multiple Providers |

| Game Type | Table Game / Live Dealer |

| RTP | 97.84% (with optimal strategy) |

| Minimum Bet | $1.00 |

| Side Bets | AA Bonus (Premium Hands) |

| Special Features | Progressive Jackpot Options, Strategy Component |

Video Poker Picks

Jacks or Better

The quintessential video poker variant offers skilled players some of the best odds available at online casinos real money platforms. Optimal strategy reduces house edge below 0.5%, making this an excellent choice for mathematically-inclined gamblers. The straightforward paytable rewards pairs of Jacks or better, with escalating payouts through Royal Flush.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Multiple Providers |

| RTP | 99.54% (Full Pay 9/6) |

| Minimum Bet | $0.25 |

| Maximum Payout | 800:1 (Royal Flush with Max Bet) |

| Strategy Complexity | Moderate |

| Special Features | Double Up Gamble Option |

Deuces Wild

Wild card excitement elevates this video poker variant above standard offerings. All four deuces substitute for any card, creating frequent winning combinations while altering optimal strategy significantly. Full-pay versions return over 100% with perfect play, representing one of few positive expectation games available at US online casinos.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Software Provider | Multiple Providers |

| RTP | 100.76% (Full Pay with Perfect Strategy) |

| Minimum Bet | $0.25 |

| Wild Cards | All Four Deuces |

| Minimum Paying Hand | Three of a Kind |

| Special Features | Wild Substitutions, Strategy Variation |

Should You Play at Online Casinos Real Money?

Deciding whether online casinos real money suit your entertainment preferences requires honest assessment of advantages, disadvantages, and personal circumstances. This balanced analysis helps inform your decision with complete information.

Advantages of Real Money Online Casinos

Convenience and Accessibility

Play anytime from anywhere with internet connectivity. No travel required, no dress codes enforced, no operating hour limitations. Mobile optimization means your favorite casino online real money games travel wherever you go—commuting, relaxing at home, or waiting in line.

Superior Bonus Value

Welcome packages at best online casinos provide value impossible to replicate at land-based venues. Deposit matches effectively double or triple starting bankrolls, while free spins and cashback offers extend play sessions significantly. Physical casinos rarely offer comparable promotional generosity.

Game Variety Exceeding Physical Limitations

Even the largest Las Vegas resorts cannot match game libraries available at top online casinos. Access thousands of slot titles, dozens of table variants, and multiple live dealer options from single platforms. New releases appear weekly without physical space constraints.

Better Odds and Higher RTPs

Lower operational costs enable online casinos to offer more favorable odds than brick-and-mortar competitors. Slot RTPs averaging 95-97% compare favorably to physical machines often set at 85-92%. Table game rules frequently favor players more generously online.

Privacy and Comfort

Gamble without judgment or observation from others. Play in pajamas, take breaks whenever desired, and manage sessions according to personal preferences rather than casino atmospherics designed to encourage extended play.

Detailed Transaction Records

Digital platforms maintain comprehensive histories of every deposit, withdrawal, wager, and outcome. This transparency aids bankroll management, tax documentation, and personal accounting impossible with cash-based physical casino play.

Responsible Gambling Tools

Modern online casinos USA provide sophisticated self-control features including deposit limits, loss limits, session timers, and self-exclusion options. These tools help maintain healthy gambling habits more effectively than willpower alone.

Disadvantages to Consider

Lack of Physical Social Atmosphere

Online gambling lacks the sensory excitement and social energy of crowded casino floors. Live dealer games partially address this limitation but cannot fully replicate the communal experience of physical venues.

Internet Dependency

Connectivity issues can interrupt sessions at critical moments. Unstable connections may cause confusion about incomplete transactions, though reputable operators maintain systems to handle disconnections fairly.

Withdrawal Waiting Periods

Accessing winnings requires processing time ranging from hours to days depending on payment methods. Physical casinos pay cash immediately, while real money online casinos require patience before funds arrive.

Potential for Excessive Play

24/7 accessibility without physical travel barriers can enable problematic gambling patterns. The convenience that benefits responsible players may disadvantage those prone to compulsive behavior.

Verification Requirements

Identity verification procedures sometimes delay initial withdrawals. Providing documentation feels intrusive to some players accustomed to anonymous cash transactions at physical casinos.

Varied Regulatory Protection

Players at offshore online casinos real money sites lack the regulatory protections available at state-licensed platforms. Dispute resolution options diminish significantly when operators function outside domestic legal frameworks.

Who Benefits Most from Online Casinos?

Ideal candidates for online casino play include:

- Players valuing convenience over social atmosphere

- Bonus-conscious gamblers maximizing promotional value

- Slot enthusiasts seeking maximum game variety

- Strategy players preferring optimal odds and rules

- Privacy-focused individuals avoiding public gambling

- Tech-comfortable users navigating digital platforms confidently

- Self-disciplined gamblers utilizing responsible gaming tools effectively

Consider alternatives if you:

- Primarily enjoy gambling’s social dimensions

- Struggle with impulse control regarding accessible entertainment

- Prefer immediate cash access to winnings

- Feel uncomfortable providing verification documentation

- Lack reliable internet connectivity

- Experience frustration with technical interfaces

Responsible Gaming at Online Casinos Real Money

Maintaining healthy relationships with gambling requires awareness, planning, and willingness to utilize available protective tools. Top online casinos provide sophisticated features supporting responsible play—using them wisely protects both finances and wellbeing.

Establishing Healthy Gambling Habits

Set Strict Budget Limits

Determine gambling budgets before sessions begin, treating these amounts as entertainment expenses rather than investment capital. Never gamble money needed for essential expenses including rent, utilities, food, or debt obligations. Once budgets deplete, stop playing regardless of outcomes.

Implement Time Boundaries

Extended sessions impair judgment and increase loss probability. Set session duration limits using casino tools or personal timers. Regular breaks maintain perspective and prevent fatigue-driven poor decisions. Consider gambling a time-limited activity rather than open-ended entertainment.

Never Chase Losses

The temptation to recover losses through continued play represents gambling’s most dangerous trap. Losing streaks eventually end, but chasing them with increasing bets frequently accelerates losses rather than reversing them. Accept losses as entertainment costs and walk away when budgets exhaust.

Avoid Gambling Under Influence

Alcohol and other substances impair decision-making crucial for responsible gambling. Many online casinos USA actively promote drinking through marketing imagery, but intoxicated gambling consistently produces worse outcomes. Maintain sobriety during sessions for clearest judgment.

Balance Gambling with Other Activities

Healthy lifestyles include diverse entertainment sources. When gambling consumes disproportionate time, attention, or financial resources, problematic patterns may be developing. Maintain relationships, hobbies, and responsibilities outside gambling activities.

Utilizing Platform Protection Features

Deposit Limits

Configure maximum deposit amounts per day, week, or month. These hard caps prevent impulsive overspending during emotional moments. Most real money online casinos implement limit increases only after cooling-off periods, while decreases take effect immediately.

Loss Limits

Separate from deposit limits, loss limits halt play after specified losses regardless of remaining balance. This protection ensures single sessions cannot inflict catastrophic damage even if deposits remain available.

Session Time Limits

Automatic reminders or forced logouts after predetermined durations prevent marathon sessions. Regular interruptions prompt reassessment of continued play decisions.

Reality Checks

Periodic pop-up notifications display session duration and net results, countering the timeless environment casinos intentionally create. These reality checks help maintain awareness of actual gambling impact.

Self-Exclusion Programs

Temporary or permanent account blocks prevent all access during specified periods. Self-exclusion represents the strongest protective measure available, completely eliminating platform access when gambling becomes problematic.

Cooling-Off Periods

Shorter than full self-exclusion, cooling-off periods provide brief breaks (24 hours to several weeks) allowing perspective recovery without permanent account closure.

Recognizing Problem Gambling Signs

Warning indicators requiring attention:

- Gambling with money allocated for essential expenses

- Borrowing money or selling possessions to fund gambling

- Lying to family or friends about gambling extent

- Feeling restless or irritable when not gambling

- Gambling to escape problems or relieve negative emotions

- Returning to gamble after losing to recover losses

- Jeopardizing relationships, employment, or education due to gambling

- Relying on others to provide money for gambling-caused financial crises

Resources for problem gambling assistance:

- National Council on Problem Gambling – 1-800-522-4700 (24/7 confidential helpline)

- Gamblers Anonymous – www.gamblersanonymous.org (support groups)

- National Problem Gambling Helpline – Text or chat available

- State-specific resources – Many jurisdictions maintain dedicated assistance programs

Seeking help demonstrates strength, not weakness. Problem gambling responds well to treatment when addressed proactively. If gambling negatively impacts your life, reach out to qualified professionals immediately.

Final Verdict: Is Playing at Online Casinos Real Money Worth It?

Online casinos real money platforms offer legitimate entertainment value for players approaching gambling responsibly. The combination of unmatched convenience, superior bonus value, extensive game variety, and favorable odds creates compelling advantages over traditional alternatives—when players maintain appropriate perspective and control.

Our recommended best online casinos demonstrate consistent excellence across security, fairness, and reliability metrics. These platforms invest substantially in player protection, game quality, and service excellence, creating environments where entertainment value justifies participation. Tens of millions of players enjoy casino online real money gaming safely as regular leisure activity.

However, gambling remains fundamentally a paid entertainment expense rather than income source or investment strategy. House edges ensure casinos profit over time regardless of short-term player outcomes. Approaching gambling with entertainment mindset—setting strict budgets, expecting losses, celebrating wins as bonuses rather than expectations—maintains healthy perspective essential for sustainable enjoyment.

The verdict: Yes, online casinos real money provide worthwhile entertainment for appropriate audiences. Players who set firm limits, utilize responsible gambling tools, select reputable platforms, and maintain balanced lifestyles find genuine value in digital gambling’s convenience and variety. Those prone to compulsive behavior, financial instability, or gambling-related problems should avoid participation entirely.

Choose platforms from our vetted recommendations, claim welcome bonuses maximizing starting value, explore diverse game categories discovering personal preferences, and most importantly—gamble responsibly within sustainable limits. The top online casinos detailed throughout this guide deliver exceptional experiences for players approaching them appropriately.

Market Evolution and Future of Online Casinos Real Money

The online casinos real money industry continues evolving rapidly, with technological innovations and regulatory developments reshaping player experiences throughout 2026 and beyond. Understanding these trends helps players anticipate upcoming opportunities and make informed platform selections.

Technological Advancements Transforming Online Gambling

Mobile-First Development Priority

Smartphone gambling now dominates real money online casinos traffic, with mobile devices accounting for over 70% of total player activity. Leading operators have shifted development priorities accordingly, designing experiences specifically for touchscreen interfaces before adapting them to desktop environments. This mobile-first approach ensures optimal performance on the devices most players actually use.

Live Dealer Gaming Expansion

Real-time streaming technology continues advancing, enabling increasingly immersive live casino experiences. Multiple camera angles, HD video quality, and interactive features bridge the gap between digital convenience and authentic casino atmosphere. Top online casinos now offer dozens of live dealer tables spanning blackjack, roulette, baccarat, poker variants, and innovative game show formats.

Cryptocurrency Integration Acceleration

Digital currency adoption at casino online real money platforms has accelerated dramatically. Beyond Bitcoin, leading operators now accept Ethereum, Litecoin, Dogecoin, and numerous altcoins. Blockchain technology enables near-instant transactions, enhanced privacy protection, and reduced processing fees—advantages driving increased player adoption across all demographics.

Artificial Intelligence Implementation

AI-powered systems personalize player experiences through customized game recommendations, tailored bonus offers, and proactive problem gambling detection. Machine learning algorithms analyze playing patterns to identify concerning behaviors before problems escalate, representing significant responsible gambling advancement.

Regulatory Landscape Developments

State-Level Legalization Progress

Additional US states continue evaluating online casino legalization following successful implementations in existing regulated markets. Legislative progress varies by jurisdiction, but industry observers anticipate expanded legal online casinos USA availability throughout coming years as tax revenue evidence accumulates from operating states.

Enhanced Consumer Protections

Regulatory frameworks increasingly emphasize player protection through mandatory responsible gambling tool requirements, advertising restrictions, and operator accountability standards. These developments benefit players through improved safety while challenging operators to maintain compliance across evolving requirements.

International Cooperation Initiatives

Cross-border regulatory coordination improves oversight of operators serving multiple jurisdictions. Information sharing agreements help identify problematic operators while streamlined licensing processes reduce barriers for legitimate companies expanding into new markets.

Emerging Gaming Innovations

Virtual Reality Casino Experiences

VR technology is beginning to transform how players interact with online casinos real money platforms. Immersive three-dimensional casino environments enable virtual table seating, social interaction with other players, and explorable gaming floors—experiences impossible through traditional interfaces. While adoption remains early-stage, VR casino development accelerates as hardware becomes more accessible.

Skill-Based Gaming Integration

Hybrid games combining traditional chance elements with player skill components attract younger demographics seeking greater outcome influence. These innovations retain casino excitement while providing strategic depth appealing to video game-experienced audiences.

Personalized Gaming Environments

Advanced customization options allow players to tailor interface appearances, sound settings, and gameplay preferences according to individual tastes. This personalization extends beyond aesthetics to include customized bonus structures, preferred game categories, and communication preferences—creating genuinely individualized experiences.

FAQs About Online Casinos Real Money

The best online casinos real money for USA players in 2026 include SlotoCash Casino, Captain Jack Casino, Slot Madness, BetWhale, Las Atlantis Casino, Decode Casino, Slots of Vegas, Raging Bull Casino, Candyland Casino, and Donbet. These platforms have earned top recommendations through verified security, reliable payouts, generous bonuses, and extensive game libraries. Each operator demonstrates consistent excellence across critical evaluation metrics including licensing compliance, withdrawal processing speed, customer service quality, and overall user experience.

Yes, players absolutely can win real money at legitimate online casinos real money platforms. Every game produces genuine cash outcomes—wins accumulate as withdrawable funds while losses reduce account balances. Thousands of players win daily at real money online casinos, from modest slot payouts to life-changing progressive jackpots exceeding millions of dollars. However, house edges ensure casinos maintain long-term profitability, meaning most players lose over extended periods. Gambling should be approached as paid entertainment where wins provide pleasant surprises rather than expected outcomes.

Online casinos real money legality varies by state within the United States. Fully regulated and licensed online casino operations currently exist in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Michigan, West Virginia, Connecticut, and Delaware. Players in these states can legally access state-approved US online casinos with full regulatory protection. Players in other states often access offshore casino online real money platforms operating from international jurisdictions, which exist in a legal gray area without explicit federal prohibition but lacking domestic regulatory oversight.

Depositing at online casinos real money platforms involves selecting payment methods from casino cashier sections. Common options include credit/debit cards (Visa, Mastercard), e-wallets (PayPal, Skrill, Neteller), cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin), bank transfers, and prepaid cards. Navigate to the deposit section, choose your preferred method, enter the amount, and confirm the transaction. Most methods process instantly, allowing immediate gameplay. Minimum deposits typically range from $10-$30 depending on platform and payment method selected.

Withdrawal processing times at real money online casinos vary significantly by payment method and platform. Cryptocurrency withdrawals typically complete within 1-24 hours, representing the fastest option available. E-wallet withdrawals usually process within 24-48 hours. Credit and debit card withdrawals require 3-5 business days. Bank transfers may take 5-7 business days for completion. First withdrawals often require identity verification, potentially adding 24-72 hours to initial processing. Our recommended top online casinos prioritize fast payouts, with many completing withdrawals within 48 hours across most payment methods.

The best payment method for online casinos real money depends on individual priorities. Cryptocurrency offers the fastest withdrawals and enhanced privacy, making it ideal for players prioritizing speed and anonymity. E-wallets like PayPal provide convenience and reasonable speeds with familiar interfaces. Credit cards offer simplicity but slower withdrawals and potential banking complications. Bank transfers accommodate larger transactions but require patience. For most players seeking balance between speed, convenience, and accessibility, e-wallets or cryptocurrencies represent optimal choices at casino online real money platforms.

Online casinos real money bonuses provide additional value through various promotional structures. Welcome bonuses typically match deposit percentages—a 200% match on $100 provides $200 in bonus funds ($300 total). Wagering requirements specify total betting volume needed before bonus funds become withdrawable (e.g., 30x requirement on $200 bonus requires $6,000 in total wagers). Free spins provide complimentary slot plays with winnings subject to similar requirements. Cashback returns percentages of net losses. Understanding bonus terms—wagering requirements, game contributions, time limits, maximum bets—ensures realistic expectations regarding actual bonus value at best online casinos.

Legitimate online casinos real money platforms utilize Random Number Generator (RNG) technology ensuring completely random, unpredictable outcomes. Independent testing laboratories including eCOGRA, Gaming Laboratories International (GLI), and Technical Systems Testing (TST) audit casino software regularly, certifying RNG functionality and verifying published payout percentages. Certified platforms display testing agency badges linking to verification reports. Licensed online casinos USA submit to regulatory oversight ensuring ongoing compliance with fairness standards. Players should verify licensing credentials and testing certifications before depositing at any platform to ensure genuine randomness and fair gameplay.

Games with the best odds at online casinos real money include video poker variants like Jacks or Better (99.54% RTP with optimal strategy) and Deuces Wild (100.76% RTP with perfect play), blackjack (99.5%+ RTP with basic strategy), baccarat banker bets (98.94% RTP), and French roulette (97.3% RTP). Slots vary widely, with premium titles offering 96-98% RTP while some budget games drop below 94%. Generally, skill-based games with strategy components offer better odds than pure chance games. Always verify specific RTP percentages for individual games at your chosen top online casinos as configurations may vary.

Choosing safe online casinos real money platforms requires evaluating several critical factors. Verify active gambling licenses from recognized authorities (Malta Gaming Authority, UK Gambling Commission, state gaming commissions, Curaçao eGaming). Confirm SSL encryption protecting data transmission. Check for independent RNG certification ensuring fair games. Research player reviews regarding payout reliability and customer service quality. Evaluate responsible gambling tool availability. Review terms and conditions for reasonable bonus requirements. Our recommended real money online casinos satisfy all safety criteria through rigorous vetting, providing pre-verified options for players seeking trustworthy platforms without conducting extensive independent research.

Yes, virtually all modern online casinos real money platforms support mobile gameplay through responsive websites or dedicated applications. Mobile-optimized sites automatically adjust layouts for smartphone and tablet screens, providing full functionality without downloads. Native iOS and Android apps offer enhanced performance and convenient home screen access. Top online casinos ensure complete feature parity between desktop and mobile experiences—deposit, play any game, withdraw winnings, contact support, and manage accounts seamlessly from mobile devices. Some platforms even offer exclusive mobile bonuses incentivizing smartphone and tablet play.